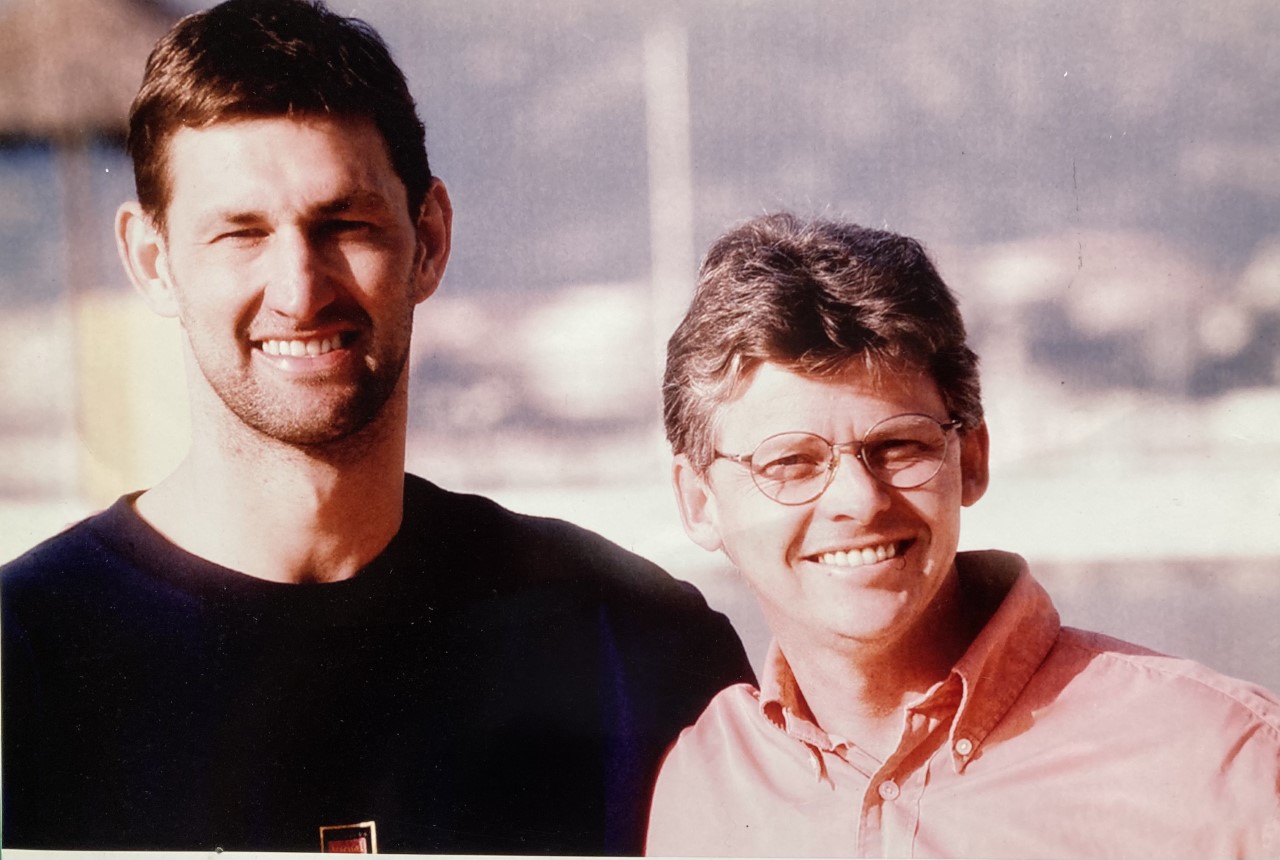

Floodlit Dreams publisher and author Seth Burkett is currently playing professional football in Sri Lanka. Throughout his time he’ll be blogging on the Floodlit Dreams website and writing a weekly column in the Non-League Paper. Below is an extract from his diary of his first game in the North East Premier League.

Priyan believes we’ll win easily. Mannar, our opponents, are ‘no problem’, he assures us. He knows their players and knows that we are better.

The only team we may have an issue with is Valvai, he tells us, who we play second. They’ve invested lots of money and have four national team players.

I appreciate his optimism, but still want to wait and see the standard before deciding whether to believe him or not.

We eat at midday and arrive bang on time. The nerves are clear. Thaabit refuses food, too nauseous to get anything down. The players that meet us at the ground are like nervous balls of energy, bouncing all over the place. They’ve done a good job, though. The lines have all been painted, the nets and corner flags are up and giant posters of myself and Dean have been hung from the stands.

The changing room has also been decorated. Thaabit allows all players three minutes to take as many selfies as they want, then insists they put their phones away until the game has finished.

Ask a Sri Lankan to take a selfie and they aren’t likely to refuse.

It feels like a fashion shoot. Each player has their own chair with their kit immaculately laid out and a sticker of their face plastered on the wall above. On one wall lies the table from last season, which Thaabit has printed to try and motivate the squad.

Mannar, I note, lost just one of their eleven games the previous season, conceding only eleven goals. Trinco, meanwhile, conceded 44 and lost seven.

Already I’m skeptical of Priyan’s words.

We’re left to get changed. Then, all of a sudden, Thaabit rushes in. ‘Go! Go! Go!’ it’s like an army drill and he’s the sargeant: excited, nervous, impatient.

‘These boys need to calm down,’ Dean notes. He’s not wrong.

On the other side of the pitch Mannar are also going about their work. I note their soft touches of the ball, their confident control, and know we’re going to be in for a tough match. They’re tall, too. Not like the Sri Lankans I’ve met before.

In the tunnel I get a closer look. When they finally arrive, that is, because Thaabit sends us out at 3.20. We stand and wait and it’s so boring, though it also helps any teammates’ excessive adrenaline settle. Our opponents provide a bit of interest. Many of them stare at me and point in my direction. I don’t know what they’re saying. At least three are taller than me and also more built. It looks like there’s going to be a serious imbalance at set pieces.

The two teams remain in the tunnel. We wait but I don’t know what for. 3.30 comes and goes. So does 3.45. We chat amongst ourselves. Sakhti goes one further.

Nobody in Sri Lanka, it seems, is aware of the age old trick where you tap someone on the chest, then move your hand up to slap their face when they look down. I’ve done it repeatedly to all of my teammates and now Sakhti has picked on the tallest, biggest opponent and told him there’s something on his chest. He looks down and Sakhti slaps him.

We go wild.

1-0 to Trinco.

Almost half an hour late, the game starts. And then it really is 1-0. Within three minutes Sakhti robs the ball from an opponent and squares to Dean, who plays in Aflal for a one on one. He makes no mistake.

My whole body tingles. It’s strange. Usually when my team scores I stay calm, fully aware of the vulnerability of a lead. Yet now I’m charging toward Aflal with my arms open wide and screaming.

Football, eh?

The crowd shrieks and whistles. About 100 people are in the stands and on the touchline with several armed policemen watching over them. Chinna is one of those on the touchline. He’s come with a group of former players, many of whom are hoping to see us lose today. ‘Good luck,’ one had told coach Rimzy before the game, ‘with players like Banda you have no chance of winning.’

Mannar don’t panic. They stick to their game plan of passing it out from the back and through midfield, which is commendable given the terrible pitch, which has been swept and watered but appears to have acquired more stones and less padding from sand as a result.

We do the opposite. I try and kick long but can’t get my foot under the ball on the hard, uneven surface. It plays with my mind. Meanwhile, Ranoos in goal launches his drop kicks as high as possible, fully aware that it isn’t only hard to deal with, but is also the best chance of creating a funny bounce that could lead to the goal.

We kick high, Mannar pass short. We play ugly, Mannar play beautifully. They’re a good team, that much is clear. The equaliser is inevitable, if not questionable. A little dink aimed between Jai and Vithu on the right side of defence sets their striker free. He lobs the ball over Ranoos but it hits the bar. I’m waiting for the rebound when the other striker careers into me, sending me flying. A sharp twinge spreads through my knee with tingles running all the way through my leg down to my ankle. I hit the ground and am vaguely aware of my surroundings. Shouts of offside, footsteps, more kicks, then, eventually, the ball in the back of the net. Then the referee is next to me. Offside, offside, I hear the calls. He sends for our physio, Matthu, who hits me with some magic spray. I limp to the side as the game restarts unsure what’s just happened. It isn’t until half time I find out that the goal was allowed.

And still there’s time for one more. Mannar dominate the play with wave after wave of attack. I give away a silly free kick, trying to reach my right leg around the striker to clear the ball he’s shielding. From the resulting free kick another ball is clipped between Jai and Vithu, who play for offside. I desperately chase after the striker. I’m gaining on him. He’s slowing, taking a touch, then another, then another. On this surface, nothing but full certainty will do. I’m within a metre of him. I could slide but don’t think it’s safe enough. Too late. He’s let fire.

The striker is no more than twelve yards out. For some reason, Ranoos is planted to his line. The ball arcs through the air and straight into Ranoos’s gloves. Then it’s straight out of his gloves and into the path of the other striker, who taps in. He’s at least five yards offside but no amount of protest will change the linesman’s decision. The goal stands.

Thaabit remains calm at half time. He must have used up all of his nerves in the first half. He tells the boys they’re playing well and to keep going.

Keep going they do. We control the second half. Our opponents continue to try and play out from the back but rarely breach our defence.

By now the crowd has swelled to at least 400. They’re in the shade behind the goal, hugging the touchline and cheering in the stand. When we get the ball in an advanced position they go wild. I even get delirious cheers when I kick the ball out of play to concede a throw in from a dangerous attack.

I’ve never played in front of such an excitable crowd.

So when Banda taps home to make it 2-2 it’s no surprise that they go crazy. And when Banda lashes home an unstoppable thirty yarder everyone loses it. The ball hits the net and he’s running and running and the fans are on the pitch and chasing him and he jumps into Thaabit’s arms. The squad catches him and we’re all together laughing and smiling and high-fiving.

We don’t deserve the win. But none of that matters when the final whistle blows. Priyan collapses to the floor in joy. Just 24 hours earlier he’d told me that it was ‘impossible’ that Banda would score. The linesmen sprint to join the referee in the middle. And the crowd sprints to us. I’m being hugged from all angles, grown men are missing my forehead and my hands. It’s pure madness. Someone lifts me up. ‘The best player’, they say, ‘amazing,’ ‘very good header’ say others. They really are getting carried away. I spot my oldest friend, a man in his late seventies who watches our every training session at the stadium, running laps around the perimeter while we work and then joining in with the kids’ game in the corner. Every time we see each other we hug, but this time he runs up to me and I lift him up and spin him round and round. It seems everyone cheers that special moment. I’ve never known such a buzz.

It takes several minutes to break through the crowd and get to the dressing room, but almost immediately we’re shepherded back out for the presentation. A novelty sized cheque for 25,000 LKR greets us, along with a 5,000 LKR one for the man of the match.

Who else? It’s Banda.

Leave A Comment